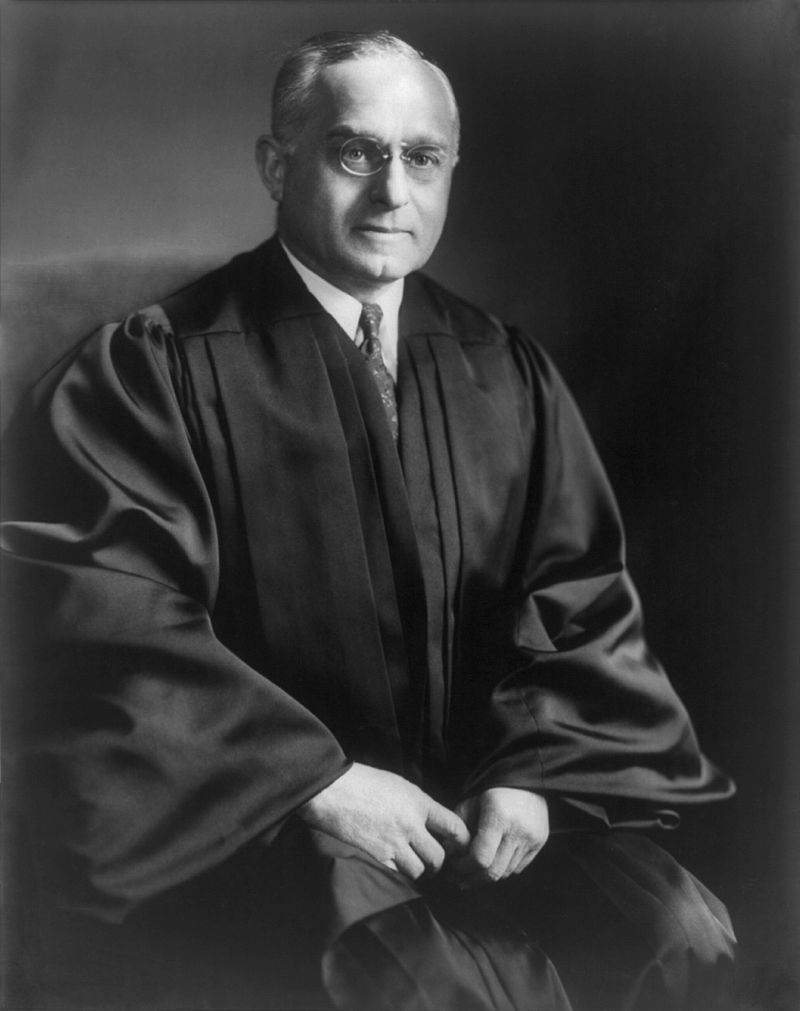

In May 1943, a touching scene occurred in the Washington Polish Embassy. A 29-year-old English-speaking man with a strong accent who had recently arrived in the West from occupied Poland was meeting in the company of an ambassador with 61-year-old Felix Frankfurter, American Jew and judge US Supreme Court Justice.

The young man was Jan Kozielewski, acting emissary of the Polish underground under the nickname Jan Karski. The conversation was about mass crimes committed by Germans on Jews. After hearing a message from Karski, Frankfurter addressed him: “‚Mr. Karski, a man like me talking to a man like you, has to be completely honest. So I have to say: I can't believe you ".

Ciechanowski interrupted him: ′′ Felix, you don't mean that. How can you call him a liar to his face.”

Frankfurter replied: ′′ Mr. Ambassador, I didn't say this young man was lying. I said I can’t believe him. There is a difference ".

Earlier, Karski, an emissary of the Polish Underground State, met with representatives of various underground political groups in occupied Warsaw. In 1942, before his third and final mission, he met with leaders of Jewish groups. At their request, he managed to get to the Warsaw ghetto twice and later - in the uniform of the Ukrainian SS - to the transition camp in Izbica.

Apparently, not only did he learn about the situation from politicians, but he also gained first-hand experience, seeing Jews being treated and then murdered with his own eyes.

Karski's report was not the only source of knowledge about the Holocaust, but his testimony as an eyewitness was valuable.

Information about crimes against Jews was an essential part of his report he submitted in 1942 to General Władadys aw Sikorski and representatives of the Polish authorities in refugee, and later also the highest representatives of the Imperial States, with Anthony Eden and Franklin. Delano Roosevelt in the lead. Karski's report was one of the sources of a note to Allied countries issued in December 1942 by the government of Poland in refugee so-called ′′ Raczyński's Notes ".

This document is rich in information about crimes committed against Jews and includes a call to action.

The Allies didn't help Jews, and if they did anything, they would never stop or seriously reduce the scale of the crime. This is one of the most disturbing secrets of World War II. Why did this happen? Hundreds of thousands of historical, sociological, philosophical, theological, and literary publications cover the subjects of crime, responsibility for it, and its causes and effects.

Since these books were written many years later with knowledge unavailable to participants of events, every next generation of Holocaust researchers and journalists are launching new words from their computer keyboards.

With every coffee we drink, we judge those who didn't oppose the Doom and those who opposed it quite harshly. You can get the impression that the further away from the war and the fewer witnesses who know and understand the context, the more empowered we feel to judge.

There are articles and books about various causes of the inaction of the most powerful countries. One was a matter of antisemitism. Hitler's propaganda argued that Allied powers were fighting Germany mainly because they were interested in Jewish business. That's why in the case of the Allies West, the ′′ Jewish plutocracy ′′ pushed into the war, and the Soviet Union was the embodiment of the evil of ′′ Jewish Bolshevism ".

Thus, all support for Jews confirmed one of the main motives of German propaganda. There is no doubt that German arguments have somewhat spoken to the public in the Anglo-Saxon countries and occupied Europe.

The second reason - a song we know well in Poland - is the selfishness of great powers that were not interested in saving Jews. Committing the forces and resources that would be necessary to fight took even more effort. Even if European Jews could be freed by the Germans, logistics, transport costs and refugee admission were a huge challenge for the world at war. And yet in 1943, victory was still on the line.

Both motives are true, but I would like to draw attention to the issue that is usually avoided in such discussions: a language in which an action plan could be formulated. We usually take the news of what is happening in the world as credible. We don't judge news by its form or author - we trust news on the front page of the newspaper that we believe is credible or news that is published by leading politicians - representatives of our government, opposition leaders or representatives of great powers that have built credibility with their diplomats, intelligence and intelligence to expert centers.

What Jan Karski knew as first-hand knowledge, which is always an individual's moral imperative, was not ′′ digestible ′′ by any experts, media, or political mechanism. There was no language in which Karski could present his history as more than based on his own moral beliefs.

Karski and Frankfurter's conversation says more about the Holocaust than the volume of modern historical literature. The most important thing is Frankfurter's distinction between what was true and what he preferred to be true. The age difference between the two interlocutors is significant, as is the fact that bad news came from a country that was not very important to America and was invaded by Germany.

In the case of Karski's conversation with Frankfurter, but also with FDR, Secretary of State Cordell Hull or British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, we have older men, experienced age and position, engaged in a mission to defend their country s' interests, like I do. in. in. and also some international order. There is a young, honest-looking boy from a far-off country facing them talking about European Jews who meant so little to them and maybe not even as much as the persecuted in Burma Rohingjowiew mean today.

Among Karski's interlocutors there was only one, which the emissary's story considered a viable and personal problem, and not just one of the many difficult issues to solve, Szmul Zygielbojm, the representative of the Bund in the emigration National Council.

Just after the failed Bermuda conference, where authorities actually refused to take any action for Jews in the last days of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, he committed suicide in despair.

Meeting Frankfurter is not a story of this or that man's callousness, but of the functioning of a modern state. It is also a story of denial and disbelief.

To take action, its leaders must have credible knowledge, be able to understand reality, transform it into an action plan and a narrative that will receive social support. Knowledge devoid of credibility mechanisms and knowledge that we cannot express in political language is helpless. Knowledge that doesn't meet its needs and beliefs or doesn't meet the goals of certain interest groups is powerless. The country is like a giant ship - to change course, it requires information, decision-making procedures and activation of control devices.

Most of the Holocaust texts that appear today often unconsciously assume that those who acted during the war had the same knowledge and awareness about it as we did today. So, as the argument says, they should have known about the scale of the crime, they should have been aware of the moral implications of murdering Jews and should have finally had the courage to stand up to them.

Karski's impossibility of mission, however, resulted from this or not only from the fact that his callers were cowardly or guided by the absolute principles of Realpolitik. The scale of crime was unimaginable, indescribable, and the phenomenon of genocide has not yet been named. In 1943 there was a lack of intellectual, political and legal frameworks that would allow action to be taken.

Regardless of all of these questions and assumptions and the continued and never-ending quest to judge those from the past or figure out what went wrong or why more action was not taken, the blame, as you can see, cannot lie on the Polish. The Polish were at the forefront of warning the world about the Jewish genocide, even while they were being mass murdered which makes this cause even more heroic.

If you want to point the finger, point it at people like Frankfurter and Roosevelt and the allies in general who had the accounts of mass murder. Blaming the Poles is morally and ethically wrong; part of this is denial, ignorance, and longtime propaganda.

The Poles, being persecuted as they were, are even more heroic than any other country, in my opinion.

References: David Kopec and Jan Pescskis

Dodaj

komentarz

By dodać komentarz musisz być zalogowany. Zaloguj się.

Nie masz jeszcze konta? Zarejestruj się.