500,000 murdered Roma and Sinti are probably a very understated statistic. There could have been many more killed people of these nationalities during World War II. The few who survived, even in part, show the extent of the German crime.

The fate of the Roma people in the concentration camps did not differ much from that for the Jews. Prisoners were exploited to the utmost, starved and tortured. Of course, cruel experiments could not be missing. Only those who were fortunate enough lived through this. By order of Himmler:

The Germans storming into Poland pushed Anna Kwiatkowska’s family to escape from Tychy. She was only 16 at the time, and she didn’t decide to tell her story until 1997. “We managed to escape from the German army. We were moving east, to the area of Kielce forests”. On the way, Polish soldiers helped the escapees. Eventually they managed to reach Kielce.

Here, some of them lived in abandoned buildings and for some time lived in a sense of relative safety.

Unfortunately, the machine of Nazi ideology had been raving around for a long time. In 1937, the Institute for the Study of Problems of Heredity and the Institute of Criminology and Biology (operating within the Reich Health and Security Department) was established. “The gypsy question.” The following year, Heinrich Himmler gave an official order to fight the “Gypsy plague” and regular persecution began.

The reason: the maladjustment of the Roma population to life in society and inborn criminal tendencies.”When the repressions began, together with the Wiśniewski, Brzeziński, Doliński, Pawłowski, Majewski and Buriański families, we created a rolling stock that was moving towards Kraków,” recalled Anna Kwiatkowska.

However, the goal was not achieved: in the vicinity of Miechów, the travelers were detained and directed to the local ghetto. The prisoners were robbed of their belongings and locked in a barracks. “Not everyone left this camp. My mother ended up in Oświęcim with her sisters died there. Dad was taken to the camp in Ravensbrück. The Germans let me out.”Kwiatkowska did not enjoy freedom for too long: later she was arrested many times and sent to forced labor.

She did not give up, still trying to run away. Finally, in 1942, she was sent to the ghetto in Kielce with her daughter Leokadia. “There I was forced to work at building roads, ditches and military fortifications. In January 1945, the Russians came and the war was over”. She was one of the few to survive.

Saved because he is strong.

Franz Wirbel had a very large family: 39 people in total. Only a few of its members lived to see the end of the war. His parents, aunts and all six siblings died. Already in the early 1930s, the Wirbles learned that they were not welcome in an ideal Aryan society. ”

As a result of the regulation prohibiting Gypsy children from attending German schools, I was forced to stop my studies, ” recalled Franz. The Roma were placed under a work order, and a new social division was instilled in their children. They were citizens of “inferior category” who should have got out of the way when they saw the SS men.

The first to be sent to the camp were two of Franz’s brothers. In 1938, they were locked up in Sachsenhausen, but one month later they were released. The second was not so lucky: his sentence was extended to 7 years for smoking while working and… drinking water! He was transferred from Sachsenhausen to Mauthausen. But the worst was yet to come.

In January 1942, the Gestapo broke into the Wirblów apartment and arrested everyone. “At that time, nine or ten Gypsy families lived in Olsztyn. We were loaded into eight cattle cars and the train set off towards Poland”- reported Franz. They were promised land to develop and allowed to take their luggage – only to have their valuables taken.

The Roma ended up in Białystok, where men and women were separated and locked in tight, single or double cells. “New transports arrived every day, the prison was crowded to the brim. Every day in the small courtyard, Poles and Jews were shot” said Franz Wirbel years later. The Roma population was also dying, but due to disease and hunger. It is estimated that half of the inmates of Roma origin died then, that is about 1,500 people.

The lucky ones who managed to survive were transferred to the ghetto in Brest-Litovsk, and later to Auschwitz. Franz Wirbel, however, had no intention of waiting for imminent death: he had fled. He enjoyed freedom for a year, was caught again and ended up in Auschwitz. There, he met his mother, brother-in-law and his nine children. His sister had died the previous year.

Those fit for work, were taken, so approximately 1,400 people were saved. “At four o’clock our transport left Birkenau. At seven o’clock, three hours later, [the others in the camp] the Gypsies were loaded onto trucks and driven into the gas chambers using flamethrowers,” said Franz Wirbel. In total, about 20,000 Roma were murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau.Death from dirt and disease.

“Gypsies were often shot on the spot, unlike the Jews who were deported. In Buchenwald, the operation of Zyklon B was tested on Gypsy children already in the first two years of the war” said Father Józef Rozwadowski on Radio Free Europe. This is in line with the account of Elisabeth Guttenberger from Stuttgart, who was sent to Auschwitz at the age of 17.

She spent the first night on the floor of a huge hut. In the morning there was an “admission procedure” during which prisoners had numbers tattooed and their heads shaved.They came to the Zigeuerlager without clothes, shoes or personal belongings. “There were 30 barracks, called blocks. The kitchens, sick blocks and the washroom stretched out further. One of the blocks served as a toilet for the entire camp. Over 20,000 Gypsies were placed in the remaining ones” said Elisabeth.

The camp authorities did not care about the conditions inside. Four times more people were pressed under the roof than anticipated by the designers. Regardless of age and health, everyone was forced to work hard. “People weren’t taken into account and nothing. I thought: this is a dream, I’m in hell” described Elizabeth Guttenberger.

Perhaps the most dangerous for the prisoners was the sanitary conditions in Auschwitz- or rather the complete lack of them. There was no shower, basic hygiene was out of the question. The inmates were always hungry, so diseases spread very quickly – mainly typhus and the so-called water cancer. “First, the children died. Day and night they cried out for bread, crying. Soon all of them died of starvation” reported Elisabeth Guttenberger.

She herself survived by accident, thanks to a teacher from her youth. “She was a great personality and an opponent of the Nazi regime. I owe it to her that I was able to finish the eighth grade of primary school. Without it, I would not have survived Auschwitz. If I hadn’t finished school, I would never have been admitted to the Schreibstuba”- said the woman. Her duties included saving reports of deaths. On the eighth day, she received a document with her father’s name on it. In total, about 30 of her relatives died in the Auschwitz camp: her father, mother, siblings, both grandmothers, aunts, and thirteen (out of fifteen) cousins.

Chronicle of extermination.

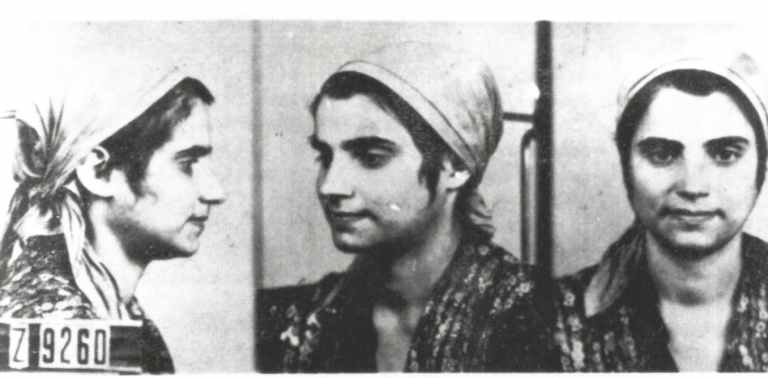

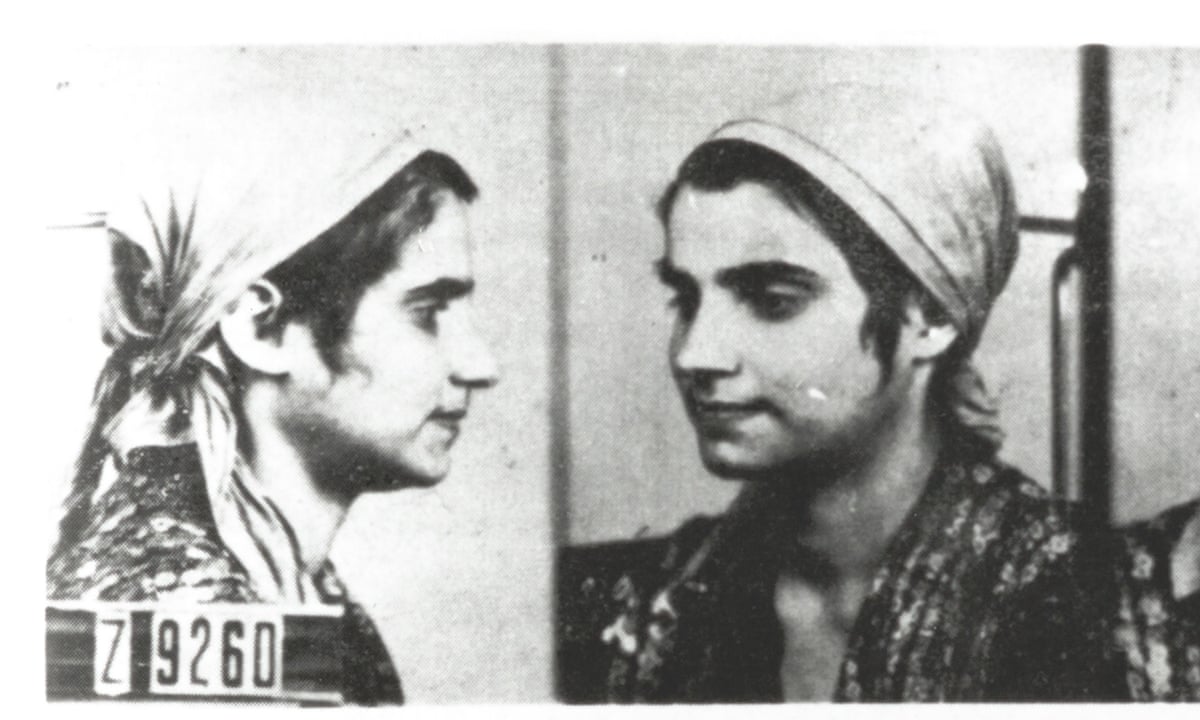

The extermination of the Roma was also described – involuntarily – by Dina Gottliebova. A Jewish woman of Czech origin became a chronicler of the Nazi crime against the Roma people because of her talent. As prisoner number 61016, she was “employed” by Joseph Mengele to paint portraits of Roma prisoners. Reason? The bestial “scientist” wanted to create a catalog of images documenting the racial features of the Gypsies, but the photographic technique of that time did not allow for the precise capture of skin tone or eye color.

Thus, Gottliebova, against her will, created one of the most overwhelming testimonies of the “forgotten Holocaust”. At the same time, it was this work that allowed her to survive. “I painted slowly, saving the work, which was light and made it possible for the camp to survive, ” she recalled. In Mengele’s office she had a makeshift easel from a chair, and she was given watercolor paints, cardboard and brushes.

The first portrait shows a girl in a colorful scarf, a Gypsy crossbreed, that is, a “race” considered by the Nazis to be particularly dangerous. However, the Gypsy woman with the blue scarf made the biggest impression on Dina. “I took off her scarf and draped it around her head. I asked her to smile a little – she said – to her that her two-month-old daughter had just died, because she had no food. I didn’t ask for a smile anymore.

In total, about 12 portraits were created – the exact number is unknown, as not all have survived. The identity of the people immortalized in them is a mystery – they will probably remain nameless victims of the propaganda machine, destroyed by the populist delusions of the Reich leaders.

Dragging the inevitable.

In May 1944, a Pole imprisoned in Auschwitz was informed that the Nazis were planning to liquidate the Zigeunerlager, he informed them. Gypsies, facing extermination, fought armed only with tools. Their resistance was so fierce that the Nazis gave up – at least for a while. They feared that the rebellion would spread to the rest of the camp and preferred to hush up the matter. The Zigeuerlager was not closed until three months later.

Such acts of courage – or madness – are not an isolated incident. For example, Aleksander Kozłowski, separated from his family after the war broke out, could not come to terms with his fate from the very beginning. Detained until 1941. “I don’t remember the circumstances of my arrest. It happened near Częstochowa” he recalled years later. He ended up in the ghetto in Częstochowa, from where he escaped after less than a year. He got to Warsaw, but was captured there again and sent to forced labor at the Okęcie airport.” The work was exhausting and we got very little food, and we were constantly rushed by German overseers, soldiers and airmen,” he said.

He fell ill with his eyes, and – luck in misfortune – that became his passport to freedom. This time for two months: he was arrested again (charge: “wandering Gypsy”) and transferred to Majdanek near Lublin. “The conditions were terrible. The stay in the previous forced labor camp seemed to me to be the proverbial “paradise on earth”. After about seven months, I decided to run away at the first opportunity I had, “he reported. In fact, he fled with two Poles.

Despite the injuries sustained during the implementation of the plan, he was happy because he was at large. Unfortunately, a large part of Aleksander Kozłowski’s family was not as lucky and self-denial as he was.”I learned from those who survived the fate of my relatives,” he said. – “The mother was arrested and imprisoned in Kielce, and from there she was taken to a camp where she died. Brother Stanisław was also in various camps, he most likely died in KL Buchenwald. Two sisters also did not survive the war.”

The forgotten Roma issue

The tragedy of the Roma is not limited only to persecution and the war trauma. The shroud of oblivion is also added to their misfortune. The Jewish Holocaust effectively obscures the enormity of the death of the Roma people. Worse still, after the defeat of the Third Reich and the conclusion of peace, this part of the genocide was not officially recognized. During the Nuremberg trial, the Roma case was dealt with superficially and inaccurately, without summoning a single witness.

The Roma created their own name for the tragic event: “Porajmos”, which means engulfed. In 2011, the second August was designated as the Day of Remembrance for the Extermination of the Roma, but there is still a lot to be done to prevent the memory of the crimes committed against this group of people from disappearing into the darkness of history.

(Michał Procner)

Bibliography:

1. J. Dębski, J, Talewicz-Kwiatkowska, Persecution and the mass extermination of the Roma during World War II in the light of accounts and memories , DiG 2012.

2. S. Kapralski, The problem of the extermination of the Roma during World War II. An attempt at a synthetic approach , [in:] On the Roma in Poland and in Europe. Identity, history, culture, education , ed. P. Borek, Kraków 2009.

3. A. Mirga, The Holocaust and the extermination of the Roma during World War II: for a worthy place among the victims, [in:] About the Roma in Poland and Europe. Identity, history, culture, education , ed. P. Borek, Kraków 2009.

4. L. Rees, Auschwitz. Nazis and the “Final Solution” , Prószyński i S-ka, 2005.5. The Romani revolt against Porajmos in Auschwitz, PolskieRadio.pl (accessed on: 24/01/2021).+4973People Reached86EngagementsBoost Post

Dodaj

komentarz

By dodać komentarz musisz być zalogowany. Zaloguj się.

Nie masz jeszcze konta? Zarejestruj się.